Antisana, 2000-2008

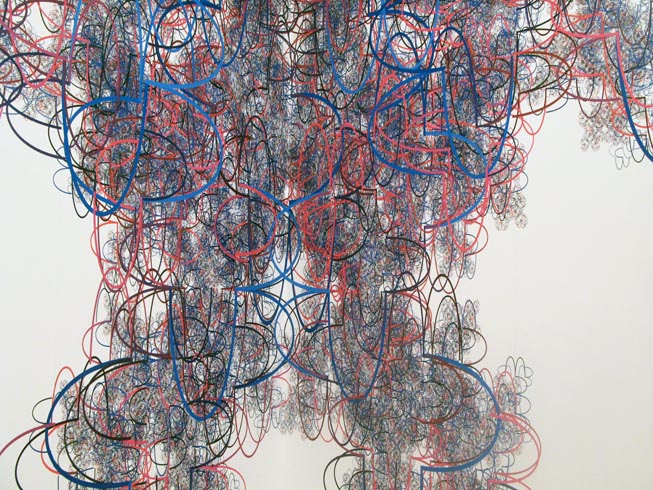

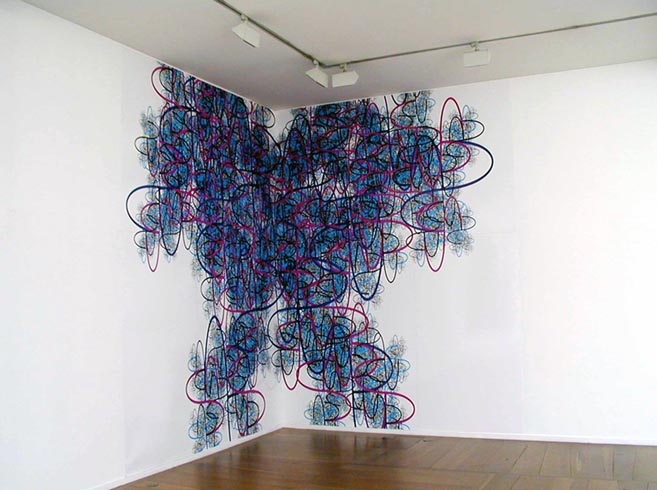

(…) Thus, inflection is the very essence of bent and mutant forms, ellipsis, spirals and folds. Endlessly virtual, it only exists in the viewer’s eyes and in the many manipulations it allows. Hence, when artworks are digital and computer-processed, as it is the case with artists such as Pascal Dombis, Yvan Rebyj or Miguel Chevalier, fractals produce a genuine culture of flux. Surfaces are then the artefacts of a phenomenon usually referred to by scientists as the “butterfly effect”, the multiplication of a swift light breathe here becoming a tornado there, in Bermuda. Like in Tatline’s art, from the outset, the forms shaped by Dombis are interlacings, ribbons and flows which cover two adjacent walls. Once computerized along a fractal progression and printed, they lead to an actual visual vertigo that dissolves in the apparent mass of details and threads, so as to follow the line-universes of the red, violet and blue curvatures even better. These vectorial fluxes actualize the differential and continuous forces of a Leibniz. Each monad contains a multiversity of worlds and expressions and the monadological space is such that every part expresses the whole, from a certain point of view. What happens then is the emergence of an aerial haptic process (haptô : touch – hold – behold) in which the interference of lines and planes creates an ever expanding and moving space over the walls. Not quite artificial, not quite natural, neither mapping nor topology, it generates a threading space of networks which functions as a visual labyrinth of rhyzomes echoing contemporary architectures with its nimbleness and a common non-organic vitalism. (…)

Extract from Le Temps Fractal, By Christine Buci-Glucksmann, 2000

(…) L’inflexion est donc le propre des formes courbes et mutantes, de l’ellipse à la spirale et aux plis. Toujours virtuelle, elle n’existe que par le regardeur et les multiples manipulations qu’elle autorise. Aussi, quand les ouvres deviennent digitales et numériques, travaillées à l’ordinateur, comme c’est le cas de Pascal Dombis, Yvan Rebyj ou de Miguel Chevalier, le fractal met en œuvre une véritable culture de flux. Les surfaces relèvent alors de ce que les scientifiques appellent « l’effet papillon ». Ou comment un léger mouvement d’air de démultipliant, produit alors une tornade dans les Bermudes… Car alors, comme dans le travail de Pascal Dombis, les formes sont d’emblée entrelacs, rubans et flux occupant deux murs en coin comme chez Tatline. Calculées à l’ordinateur selon une progression fractale, imprimées, elles engendrent un véritable vertige du regard, qui se perd dans le fouillis apparent du détail, du tressé, pour mieux suivre les lignes-univers des courbes rouges, voilettes ou bleues. Ces flux vectoriels réalisent les forces différentielles et continues d’un Leibniz. Chaque monade contient une multiplicité de mondes et d’expressions, et l’espace monadologique est tel que chaque partie exprime le tout, sous un certain point de vue. Il y a alors un haptique aérien (haptô, toucher-voir), où l’interférence des lignes et des plans crée un lieu en expansion et mouvement continuel sur les murs. Entre artifices et nature, plan et topologie, elle engendre « espace-filet » de réseaux, un labyrinthe visuel de rhizomes, qui évoque les architectures contemporaines par sa légèreté et par une même vitalisme non organique. (…)

Extrait du Le Temps Fractal, par Christine Buci-Glucksmann, 2000